On 22 April 2025, terrorists attacked Indian military and civilian targets in Kashmir, killing dozens and reigniting one of the world's most dangerous rivalries. In swift retaliation, the Indian Air Force struck nine suspected militant sites inside Pakistan’s territory and on its side of the disputed Kashmir region. Islamabad responded with military alerts and the now-familiar threats of escalation. The world watched, holding its breath, as two nuclear powers once again teetered at the edge of catastrophe. This latest crisis was not an aberration. It is the direct result of a dangerous pattern: the entanglement of nuclear weapons, terrorism, and fragile governance in Pakistan. As these escalations repeat with alarming frequency, the global community must confront an uncomfortable truth. Pakistan’s possession of nuclear weapons, under its current political and security conditions, is an unacceptable threat to regional and international peace.

Since its nuclearization in 1998, Pakistan’s military and intelligence services have treated militant proxies as tools of asymmetric warfare against India and, at times, in Afghanistan. Groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba, Afghan and Pakistani Taliban, IS-K, and Jaish-e-Mohammed, despite periodic government crackdowns, have endured and thrived. As C. Christine Fair has thoroughly documented, this strategy is embedded in Pakistan’s military doctrine, which views terrorism not as a problem to solve but as an asset to exploit.¹ While the state officially denies links to recent Kashmir attacks, the presence of such groups operating with impunity within Pakistani borders remains undeniable.

No other nuclear-armed country in the world has such a dense web of extremist organizations tolerated or enabled by elements of the state itself. As a result, every militant attack that traces back to Pakistan—whether the 2008 Mumbai attack, the 2019 Pulwama bombing, or the recent Kashmir killings—risks igniting a broader conflict between nuclear-armed states. India’s increasing willingness to retaliate, including its 2025 airstrikes, reflects both a desire to punish and a belief that measured strikes can deter further terrorism. Yet, as the world saw in February 2019 and again now, these actions can rapidly escalate, drawing both nations into dangerous standoffs.

The greatest fear is not conventional war, but the possibility of terrorist groups acquiring nuclear materials or weapons through insider access, theft, or state collapse. Numerous assessments by U.S. and international intelligence agencies have raised concerns about Pakistan’s nuclear security. While the country has taken steps to harden its facilities, scholars like Feroz Khan and Emily Burke have warned that the presence of radicalized insiders or sympathizers within Pakistan’s sprawling security apparatus cannot be fully discounted.² The Congressional Research Service has similarly noted the potential for nuclear terrorism emanating from Pakistan, either through state complicity or failure.³

Compounding this threat is Pakistan’s nuclear doctrine, which uniquely emphasizes the early use of tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs) in the event of conventional conflict. Once deployed, these battlefield weapons are far more vulnerable to unauthorized use or theft. As physicist Pervez Hoodbhoy argues, TNWs lower the nuclear threshold and dangerously decentralize command and control in crises.⁴ In the heat of escalating clashes like those witnessed in 2025, this doctrine does not deter conflict—it risks triggering it.

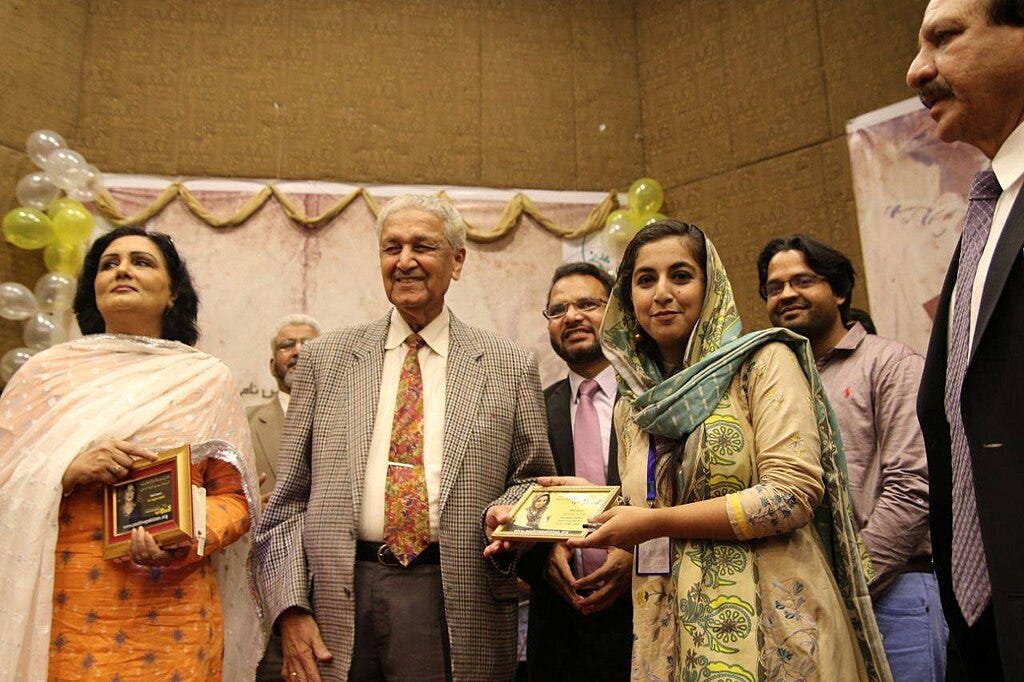

Pakistan’s past proliferation record deepens these concerns. The A.Q. Khan network, which exported nuclear technology to North Korea, Iran, and Libya, proved how corruption and weak oversight can turn national arsenals into international threats (Albright and Hinderstein 2005).⁵ Although Pakistani officials assert that this network was dismantled, recent evaluations by the Nuclear Threat Initiative still rank Pakistan poorly in nuclear security relative to other nuclear states (NTI 2023).⁶

Pakistan’s unstable political landscape compounds these technical and military dangers. Civilian governments remain weak, subject to military interference and periodic coups. Radicalized political factions and extremist ideologies have penetrated public institutions. Unlike in stable democracies, there is no robust civilian oversight of nuclear decision-making. Scott Sagan’s work on organizational failure and nuclear risk underscores how such weaknesses, more than irrational leadership, are often the true drivers of nuclear catastrophe.⁷

Yet international actors have largely tolerated Pakistan’s nuclear status, fearing that pressuring Islamabad could destabilize the country or drive it closer to China and Russia. This policy of benign neglect is no longer tenable. Each India-Pakistan crisis reminds the world that the cost of inaction is rising. Continued nuclear brinkmanship emboldens Pakistani-based terrorist groups, destabilizes South Asia, and threatens global security.

Denuclearization, while difficult, is not unprecedented. South Africa voluntarily dismantled its arsenal. Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine surrendered Soviet nuclear weapons in exchange for security assurances. Pakistan’s military leaders often invoke India’s conventional military superiority to justify retaining nuclear weapons. But history shows that nuclear arsenals do not prevent proxy wars, terrorist attacks, or conventional skirmishes—as the 2025 airstrikes once again proved. Instead, they provide dangerous cover for sub-state violence while draining Pakistan’s economic and diplomatic capital.

A phased denuclearization process would require reciprocal measures from India, credible international security guarantees, and significant economic incentives. Equally vital would be a comprehensive counterterrorism strategy to dismantle the militant networks that have thrived under Pakistan’s nuclear umbrella. Without such action, the risk of nuclear terrorism or an accidental nuclear war will only increase.

The costs of maintaining Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal extend beyond South Asia. In a globalized world, radioactive fallout, disrupted trade, refugee crises, and the specter of terrorism affect all nations. Scholars Zia Mian and M.V. Ramana warn that even a limited nuclear exchange in South Asia could produce catastrophic environmental and agricultural consequences worldwide.⁸

The 2025 Kashmir killings of innocents by militants and subsequent Indian airstrikes were not anomalies. They are symptoms of a deeper, structural threat rooted in Pakistan’s fusion of nuclear weapons, terrorism, and political instability. The international community must abandon the dangerous hope that luck and crisis management will indefinitely prevent disaster. Pakistan’s denuclearization, however challenging, is not merely desirable. It is imperative.

References

Fair, C. Christine. Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Khan, Feroz Hassan, and Emily Burke. "Nuclear Order in the South Asian Regional Security Complex." Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 1, no. 2 (2018): 239–256.

Kerr, Paul K., and Mary Beth Nikitin. “Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons: Background and Issues for Congress.” Congressional Research Service, 2021.

Hoodbhoy, Pervez. Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Albright, David, and Corey Hinderstein. “Unraveling the A.Q. Khan and Future Proliferation Networks.” The Washington Quarterly 28, no. 2 (2005): 111–128.

Nuclear Threat Initiative. NTI Nuclear Security Index 2023. Washington, DC: NTI, 2023.

Sagan, Scott D. "The Perils of Proliferation: Organizational Theory, Deterrence Theory, and the Spread of Nuclear Weapons." International Security 18, no. 4 (1994): 66–107.

Mian, Zia, and M.V. Ramana. "South Asia’s Nuclear Dangers." Foreign Affairs, May 2014.

BBC News. “Pulwama Attack: Why India and Pakistan Are Clashing over Kashmir.” February 27, 2019.

Council on Foreign Relations. “Pakistan’s Relations with India.” Updated March 2024.

The Diplomat. “The Perils of Pakistan’s Tactical Nuclear Weapons.” February 2023.

Reuters. “Pakistan Army’s Links to Militants Remain a Concern, U.S. Officials Say.” October 2022.